Remembering theoretical physicist James D. “BJ” Bjorken, 90, who played a crucial role in discovering quarks

His wide-ranging curiosity, novel way of looking at problems and sheer joy in solving them drove many important contributions to particle physics.

By Glennda Chui

Theoretical physicist James D. “BJ” Bjorken, a professor emeritus at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University whose work played a key role in revealing the existence of quarks and illuminating the mathematical framework that governs all fundamental interactions, died Aug. 6 in Redwood City, California, at the age of 90 after a brief struggle with metastatic melanoma.

Part of a wave of young physicists who came to Stanford in the mid-1950s to explore the most basic secrets of matter with a brand-new technology known as the linear accelerator, Bjorken went on to make important contributions not just to particle physics theory, but also to the design of experiments and the efficient operation of particle accelerators.

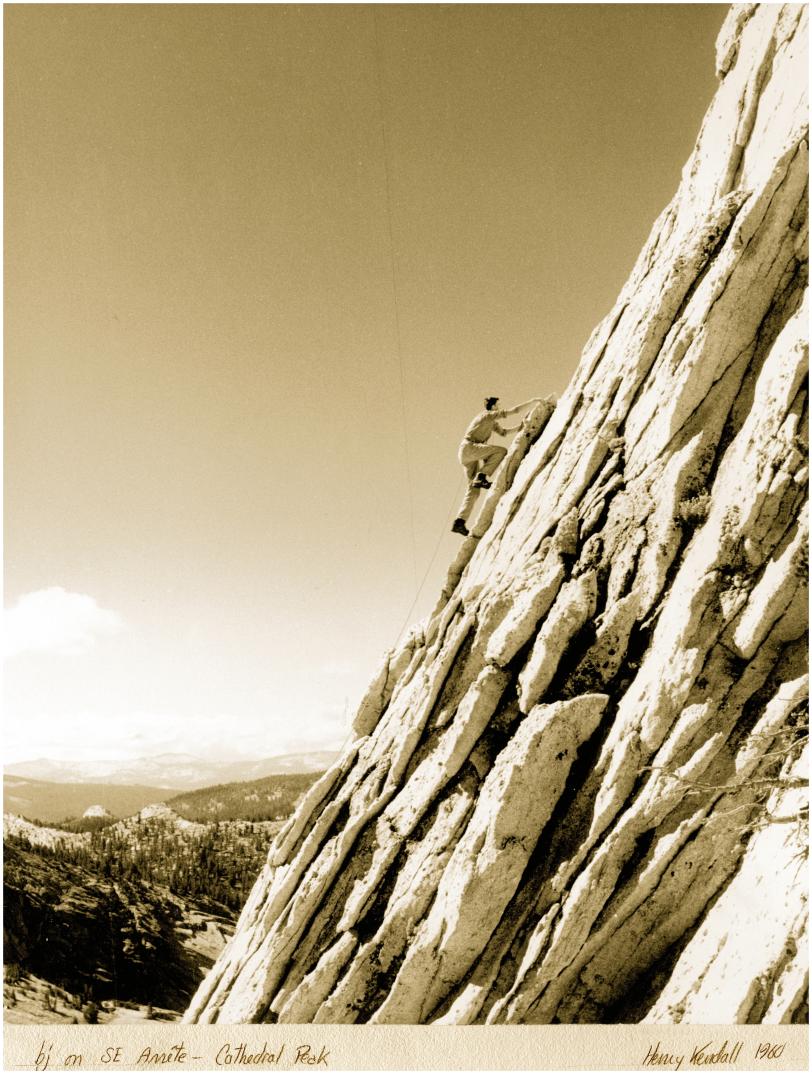

Known for his warmth, generosity and collaborative spirit, Bjorken passionately pursued many interests outside physics, from mountain climbing, skiing, cycling and windsurfing to listening to classical music. He divided his time between homes in Woodside, California, and Driggs, Idaho, and thought nothing of driving long distances to see an opera in Chicago, where he had season tickets, or drop in unannounced at the office of some fellow physicist for deep conversations about things like general relativity, dark matter and dark energy. “I’ve found the most efficient way to test ideas and get hard criticism is one-on-one conversation with people who know more than I do,” he said.

His most famous scientific achievement was the invention of “Bjorken scaling,” an analytical approach that allowed physicists to plot the data from early particle collisions at SLAC’s Stanford Linear Accelerator in a way that revealed the presence of quarks inside the proton.

“This was a huge moment in particle physics – the beginning of our understanding that quarks are real,” said SLAC theoretical physicist Michael Peskin.

But Bjorken was also known for identifying a wide variety of interesting problems and tackling them in novel ways, driven by the pure joy of doing the work.

“He was somewhat iconoclastic. He didn't march to anybody else's drum," said Lance Dixon, a theoretical physicist at SLAC and Stanford. "What made him a great physicist was he thought differently from other people.” He also had colorful and often distinctly visual ways of thinking about physics, Dixon said – for instance, describing physics concepts in terms of plumbing or baked Alaska.

Others remembered his sense of fun, like the time he gave the closing lecture at a summer physics institute dressed in a bear skin.

Helen Quinn, a SLAC theoretical physicist and professor emerita who became Bjorken’s first PhD student in 1965, said, “He never played one-upmanship. He never sought recognition for himself, and he was very generous in recognizing the contributions of others. For instance, when I was a graduate student, I found and told him about an error in one of his papers. He submitted a correction, and he made me an author of the correction. Nobody does that!”

Early days at Stanford and SLAC

Born in Chicago on June 22, 1934, James Daniel Bjorken grew up in Park Ridge, Illinois, where he attended public schools and was drawn to math and chemistry. His father, who had immigrated from Sweden in 1923, was an electrical engineer who repaired industrial electric motors and generators. Bjorken would later comment that this sort of hands-on problem solving was in his blood.

After earning a bachelor’s degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Bjorken came to Stanford as a graduate student in 1956. He was one of half a dozen MIT physicists, including his adviser and father figure Sidney Drell and future SLAC director and Nobelist Burton Richter, who were drawn by new facilities on the Stanford campus, including an early linear accelerator that scattered electrons off targets to explore the nature of the neutron and proton.

Ten years later those experiments moved to SLAC, where the newly constructed 2-mile-long Stanford Linear Accelerator would boost electrons to much higher energies needed to delve even deeper into the nature of matter.

By that time, theorists had proposed that the protons and neutrons inside the atomic nucleus contained other fundamental particles. But no one knew much about their properties or how to go about proving they were there. “People thought about them as not quite real,” Quinn recalled.

Stalking the quark

Bjorken, who had earned a PhD from Stanford in 1959 and joined the faculty in 1961, began investigating the mathematical properties of collisions where highly energetic electrons bounce, or scatter, off protons. In an influential 1969 paper, he suggested that the electrons were actually bouncing off point-like particles within the proton, a process known as deep inelastic scattering, and he started lobbying experimentalists to test it with the SLAC accelerator.

“The idea was to have electrons knock protons into smithereens as violently as you could arrange it,” he recalled in a 2015 interview. “This was not trendy at the time.” But he continued to talk up the idea with the experimental team during mountain climbing trips with the Stanford Alpine Club.

Carrying out the experiments would require a new mathematical language and Bjorken contributed to its development, with simplifications and improvements from two of his students, John Kogut and Davison Soper, and Caltech physicist Richard Feynman.

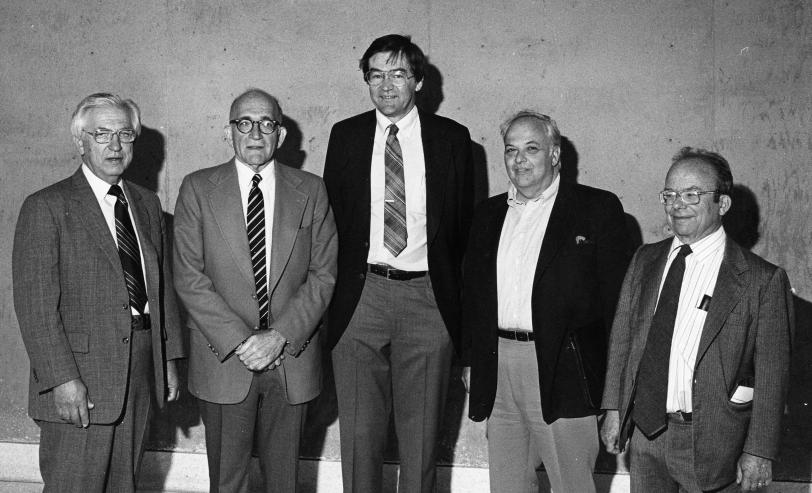

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, those experiments confirmed that the proton does indeed consist of fundamental particles called quarks – a discovery honored with the 1990 Nobel Prize in physics for SLAC’s Richard Taylor and MIT’s Henry Kendall and Jerome Friedman.

Many in the particle physics community thought Bjorken would have shared the Nobel if the prize had not been limited to three winners, Quinn said. But his role was later recognized with two of the most prestigious awards in the field: the Wolf Prize in Physics and the 2015 High Energy and Particle Physics Prize of the European Physical Society, which also honored his significant contributions to developing a theory of the “strong force” that mediates interactions between quarks within protons and neutrons.

The accelerator side of things

In 1979, Bjorken left the SLAC and Stanford faculties to become associate director for physics at the DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, saying he wanted to learn more about the accelerator side of things. In fact, he was known as one of the few particle physics theorists who also participated in experiments, both at Fermilab’s Tevatron collider and at SLAC.

He returned to SLAC in 1989, where he continued to innovate.

Over the course of his career, among other things, he invented ideas related to the existence of the charm quark and the circulation of protons in a storage ring, and he popularized the unitarity triangle – a way of graphically depicting measurements made by the BaBar particle detector at SLAC. He and Drell also co-wrote two widely used graduate-level textbooks – Relativistic Quantum Mechanics and Relativistic Quantum Fields.

In 2009 Bjorken contributed to an influential paper by three younger theorists suggesting approaches for searching for “heavy” or “dark” photons, hypothetical carriers of a new fundamental force.

Awards and honors

Bjorken was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1973. In addition to the 2015 Wolf and High Energy and Particle Physics prizes, which he shared with other scientists, he was awarded the American Physical Society’s Dannie Heinemann Prize in Mathematical Physics; the Department of Energy’s Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award; and the Dirac Medal from the International Center for Theoretical Physics.

In 2017 he shared the Robert R. Wilson Prize for Achievement in the Physics of Particle Accelerators for groundbreaking theoretical work he did at Fermilab that helped to sharpen the focus of particle beams in many types of accelerators by understanding and coping with an important constraint on their intensity and focus.

Family members said Bjorken continued to amuse himself with physics until his very last days. “He was surrounded by physics equations and thoughts,” said his daughter, Johanna Bjorken. “It was truly what he loved – and yet it was just one dimension of the many things he loved.”

Bjorken is survived by his daughters Johanna Bjorken of Brooklyn, New York and Eliza B. Davies of San Carlos, California; stepchildren Peter Nauenberg of Crystal Bay, Nevada, and Maria James of San Leandro, California; and nine grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his wife Joan G. Bjorken (1983) and granddaughter Nova Joan Adan (2024).

At Bjorken's request, there will be no formal services or memorial.

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.